>From Environmental Science and Technology, September 22, 2004

Note especially the following points:

- "Cohen tells ES&T that DOD plans to resubmit the

exemptions during the next congressional session. An internal document

leaked to the press states that exemptions to other environmental laws

are also being considered. “There was a lot of _expression_ of

legislative support,” Cohen says."

- "Nevertheless, the military has been desperately seeking cases where

environmental regulations conflict with military readiness. DOD Deputy

Secretary Paul Wolfowitz sent a letter in 2003 to all the armed

services asking for cases where environmental regulations were

interfering with national security or military readiness. To date,

Cohen tells ES&T, not a single instance has been found."

--

Steve Taylor

National Organizer

Military Toxics Project

"Networking for Environmental Justice"

www.miltoxproj.org

(207) 783-5091

The authoritative voice of the environmental research community.

The authoritative voice of the environmental research community.

Policy News - September 22, 2004

Are environmental exemptions for the U.S. military justified?

During the early 1990s, a fight began heating up in North Carolina.

Environmentalists sued the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) for failing

to protect the habitat of the endangered red-cockaded woodpecker at

Fort Bragg, home of the U.S. Army’s 82nd Airborne Division. Both sides

were meeting to try to work out a compromise, when the post commander

strode into the room and knocked the environmentalists right out of

their seats.

|

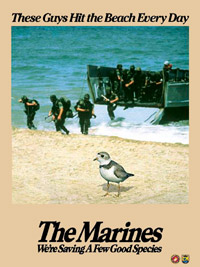

| In 1996, the U.S.

Defense Department released this poster, the first in a series touting

environmental awareness. Today, the military claims that measures to

protect plover habitat threaten marine training and war readiness. |

|

|

“I’ve been a warrior for all these years,” the general reportedly

said, “and it’s my duty to protect this country and all its

inhabitants, including its endangered species.”

This opening statement changed the whole debate, says Ray Clark,

then the Assistant for Environment with the Army. With about 161,000

acres of mostly longleaf pine, Fort Bragg soon began partnering with

local conservation groups to buy land along the edges of the post.

These buffer zones helped protect both army training areas and the

woodpecker habitat. The program quickly became a top priority as part

of DOD’s press campaign to sell the military as a fighting force that

not only protected America from threats abroad but also preserved the

environment at home.

How times have changed. Since President George W. Bush came into

office, DOD has won exemptions from sections of the laws that protect

endangered species, migratory birds, and marine mammals. The department

is now trying to win exemptions from laws covering toxic Superfund

sites, solid-waste management, and clean air. According to notes from a

2002 DOD meeting leaked to the press, the fight for these exemptions

will “require a multiyear campaign.” As a result, DOD is now battling

environmentalists and other government officials on several fronts.

Many critics of the administration say that the campaign is more about

undermining environmental laws than protecting military readiness.

The stakes are huge and highly complex. Of the 158 federal

facilities on Superfund’s National Priorities List, DOD is responsible

for 129; the projected cleanup cost for these sites is more than $14

billion. On the other hand, DOD invests $4 billion annually in

environmental protection and provides more funding for marine-mammal

research than any other federal agency. And with 25 million acres of

property, DOD houses the greatest concentration of endangered species

on any federal land. So while critics complain about the military, they

also tip their hats. The problem, they say, is that elements within the

current Bush Administration and the Pentagon are leading an unfounded

campaign against environmental laws.

“The armed services have a history they can be proud of,” says

Clark. From the Nixon to Clinton administrations, military leaders were

told they had a responsibility to balance military readiness with

environmental protection, he tells ES&T. “This

administration is a departure from that value set,” he adds.

However, others see it differently. In a Senate hearing in April

2003, Sen. James M. Inhofe (R-OK) said the exemptions are needed to

protect the lives of service men and women. “Rather than seeking

compromise, environmental groups file lawsuits, many of which could

seriously undermine training and readiness…. But despite their

unfortunate rhetoric, this proposal we are considering today is

balanced, bipartisan, rooted in common sense, and good for the

environment.”

Numerous current and former DOD officials and military leaders say

that change began in the late 1990s when the Center for Biological

Diversity, an environmental group, filed a lawsuit against the U.S.

Navy under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. The center cited the navy for

killing migratory birds during bombing on Farallon de Medinilla, a

small, uninhabited Pacific island. In an interview with ES&T,

DOD General Counsel for the Environment, Ben Cohen, said that pilot

skills degrade as aircraft carriers transit across the Pacific from the

United States. “It was the last place in the region where carrier

aircraft could train as they prepared to enter the theater of

operation,” he says.

At the same time that the Navy feared losing the Farallon as a

training site, other groups were suing the government to protect

habitat for endangered species at another naval installation,

California’s Camp Pendleton. Fearing more lawsuits, DOD sources tell ES&T

that a group of naval lawyers began pushing for legislative protection

against lawsuits when President Bush came into office; his political

appointees saw a green light to roll back environmental oversight after

September 11, 2001.

A former high-ranking DOD environmental official, who asked for

anonymity, says there are real concerns with endangered species at

Pendleton but that they could have been easily handled if the DOD

focused on other problems, such as suburban growth around military

bases. “That has not been the priority of this administration. They

have focused on how to get relief from environmental laws because they

believe they have a favorable political climate.”

The final straw for the Navy, say DOD officials, was lawsuits by

environmental groups to curtail the use of certain types of sonar.

Scientists are not exactly certain how sonar affects marine mammals,

but since 1960, numerous stranding incidents have occurred, involving

mostly beaked whales, when navy sonar was in the area. In March 2000,

17 whales beached themselves in the Bahamas at a time when navy sonar

was being used. Six later died. “It appeared from all evidence that the

whales attempted to get out of the sonar and then swam onto the beach,”

says Dan Schregardus, the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Environment in

the Navy.

In September 2002, 14 whales became stranded on the Canary Islands

just 4 hours after the onset of a naval training exercise. Necropsies

found tissue damage consistent with trauma due to in vivo gas bubble

formation (Nature 2003, 425, 575).

“It’s not clear if the sound is so loud it damages the animals

directly or if it triggers a behavioral response so that the animals

surface too quickly and get something like the bends,” says Peter

Tyack, a senior scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

“In the end, we know there is some correlation between these sounds and

the animals ending up on the beach.”

While beachings of whales have captured headlines, there are other

incidents where environmental laws and military training could be in

conflict. Cohen cites Fort Richardson in Alaska as a prime example of a

“potential train wreck.” In April 2002, a coalition of public-interest

groups and Native American tribes sent a notice of intent to file a

lawsuit against DOD for poisoning water with toxins leaching from

unexploded munitions. Cohen says DOD lawyers fear such third-party

lawsuits could force EPA to shut down live-fire ranges because the

training harms the wildlife and endangers water supplies.

“It’s not responsible for us to wait until we’re actually shut down

at a vital installation, before we go to Congress and tell them there

are troubles,” says Cohen.

However, last year former EPA Administrator Christine Todd Whitman

told Congress that there have been no incidents where the agency was

forced to interfere with military readiness. “I’m not aware of any

particular area where environmental protection regulations are

preventing the desired training,” she testified.

This was made clear during a packed congressional hearing in April

at which the DOD exemptions were strongly opposed by a host of groups,

including a group of 39 state attorneys general, local water agencies,

numerous state coalitions, and environmental groups. Under heated

questioning by Rep. John Dingell (D-MI), DOD Deputy Under Secretary Ray

DuBois admitted that there was not a single incident where Superfund,

solid-waste, or clean-air legislation had interfered with military

readiness.

There are other indications that the military has not been affected

by environmental regulations. In the late 1990s, David Henkins, an

Earthjustice lawyer who participated in the suit over bombing activity

on the Farallon, succeeded in stopping training on the Makua military

range on Hawaii’s Oahu Island for violations of environmental laws. For

three years, the military was unable to use the range and regularly

told judges and the press that lack of training was degrading

readiness. Yet, when Henkins reviewed the military training records

from the local commanders, they were pretty much the same: “ready to

perform our wartime mission.”

Nevertheless, the military has been desperately seeking cases where

environmental regulations conflict with military readiness. DOD Deputy

Secretary Paul Wolfowitz sent a letter in 2003 to all the armed

services asking for cases where environmental regulations were

interfering with national security or military readiness. To date,

Cohen tells ES&T, not a single instance has been found.

But military activities have affected the environment in numerous

instances. Forty DOD sites have contaminated groundwater or surface

water with perchlorate. In both Massachusetts and Maryland, DOD

contamination of groundwater has forced the shutdown of local wells.

The contamination in Maryland has resulted in numerous underground

toxin plumes originating from two local military installations.

Thousands of testing wells now dot the Cape Cod area, monitoring

pollution underneath this famous Massachusetts vacation spot; the total

cleanup cost is projected at about $1 billion.

“The question becomes what [DOD] would have done if they hadn’t been

required to meet [environmental] statutes,” says Ed Eichner, a

hydrologist with the Cape Cod Commission. “The main issue here, after

stripping away all the details, is that the DOD wants to become

self-regulating,” charges Sylvia Lowrance, former top administrator for

enforcement at EPA.

Cohen tells ES&T that DOD plans to resubmit the

exemptions during the next congressional session. An internal document

leaked to the press states that exemptions to other environmental laws

are also being considered. “There was a lot of _expression_ of

legislative support,” Cohen says. —PAUL D. THACKER